All Rise

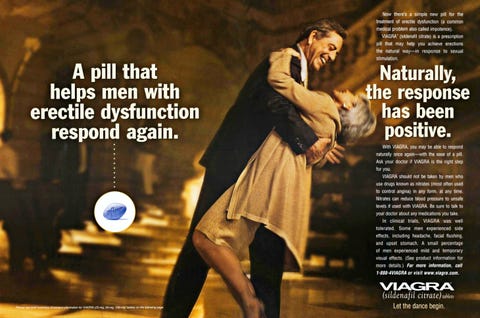

Written by David Kushner, Esquire

Tuesday August 21st, 2018

How Viagra went from a medical mistake to a $3-billion-dollar-a-year industry

According to the Chinese calendar, 2017 was the Year of the Cock. 2018 is the Year of the Dog. And, in Dog years, this is also the Year of the Cock Pill: Viagra.

The revolutionary erectile-dysfunction drug is celebrating the twentieth anniversary of its Brobdingnagian launch in a most auspicious way: by finally going generic.

The ramifications for generic sildenafil (the scientific name) are huge for your pocketbook and your health. Viagra’s high demand and cost (about seventy dollars a pill) have made it among the most bootlegged meds in the world, and one of the top sellers for Internet pharmacies. A study presented at the World Meeting on Sexual Medicine found that 77 percent of Viagra sold online was fake. Counterfeit Viagra and similar impostors have been linked to liver damage, strokes, and death. Just a few years back, former Los Angeles Lakers star Lamar Odom ended up face-planted in a Nevada brothel from coke and phony herbal fucklements. “He was taking herbal Viagra,” brothel owner Dennis Hof said at the time, “and a lot of it.” The availability of generic sildenafil cuts the price of the pills in half and promises greater assurance that the pill you pop won’t be your last.

But while Viagra is poised to go wider than ever before, the inside story of its launch is not widely known. How did a group of oddball underdogs in America’s most conservative pharmaceutical conglomerate, Pfizer, bring it into existence? At the time, the idea of selling Viagra was considered crazy at best and immoral at worst.

In fact, it’s a miracle that it ever came to be at all. In addition to the people within Pfizer who were in an uproar over the “dick pill,” four major groups began rallying against it before its launch: the Catholic church (which thought it was immoral), medical experts (who insisted patients would be too embarrassed to ask for the pill), business execs (who thought it would make Pfizer a laughingstock), and legislators (who lobbied against the pill for the same reason as the church).

It was the job of two unlikely guys at Pfizer to overcome them all: Rooney Nelson, a young Jamaican marketing whiz, and Sal “Dr. Sal” Giorgianni, a crusty Italian pharmacist from Queens who became Viagra’s medical expert. Together, Nelson and Dr. Sal became the dynamic duo of erectile dysfunction, wooing angry religious leaders, skittish politicians, and cynical pharma nerds from all over.

Against all odds, they succeeded, making Viagra one of the most successful and emulated launches of all time, and the basis for today’s $3 billion erectile-dysfunction industry. Now, on the drug’s twentieth birthday, they’re sharing their story for the first time.

When Rooney Nelson arrived for his first day of work at Pfizer’s corporate office in New York City after completing his MBA at Florida A&M, he thought it was anything but cool. Compared with Jamaica, where he was born and raised, it seemed like an “exceedingly conservative” company, filled with thousands of somber employees, many of whom wouldn’t leave their desks without first putting on a suit coat. “It was not a hip kind of place,” he says with a laugh.

Pfizer had been around since 1849 and had made its name as the chief producer of penicillin during World War II. In recent years, however, it had fallen behind larger pharmas such as Merck and Johnson & Johnson. It was looking for a break. It came, as breaks often do, when least expected. Scientists at Pfizer’s lab in the small coastal town of Sandwich, England, had made a strange discovery while testing a drug that treated chest pain by expanding blood vessels. When given the drug three times a day, volunteers were reporting muscle aches, headaches, and some discomfort while swallowing. Oh, and, as one investigator relayed to Ian Osterloh, the clinical researcher heading the study for Pfizer in 1991, some were getting hard-ons, too.

Treating erectile dysfunction had long been considered an exotic hack involving penile injections and pumps. While Osterloh was intrigued by the report of increased erections among the chest-pain-medication volunteers, it didn’t muster much of a reaction. Impotence wasn’t acknowledged as a clinical problem, he says, and if so, it was thought to be psychological, not something that could be fixed with a pill. “Nobody at that time really thought, Gosh, this is fantastic,” he recalls.

But Osterloh was among those who thought it merited more study. He can still remember his feeling of helplessness as a junior doctor at the UK National Health Service when a forty-year-old man asked if he could be treated for impotence. Osterloh had gone to his boss to inquire, only to be told there was nothing they could do.

David Brinkley, the head of Pfizer’s new product-planning group, was enticed enough by the discovery to see if it had the potential to go to market. Gay and progressive with a flair for marketing, Brinkley, like Nelson, felt he was an outlier within the staid company. And it didn’t take long after he began discussing the drug in-house to find that many didn’t share his opinion. “To have conversations about sexual-function drugs was difficult for a lot of people,” Brinkley says. “It was not considered dignified medicine.” The management told him that it was not in the business of marketing side effects—erections or otherwise.

But after enough volunteers reported getting erections from the drug, there was no doubt about it anymore: This was no side effect; this was a direct result. In 1996, Pfizer gave Brinkley the green light to bring this pill to the public. It was named Viagra, a meaningless word chosen, if anything, because drugs that started with the letter V were considered powerful-sounding.

Viagra would only work, Brinkley knew, if he could overcome the biggest—and for Pfizer, the riskiest—challenge of all: being taken seriously. It wasn’t just the outside world that presented a problem; it was the viability within the company itself. When Nelson first heard from Brinkley about the “dick pill,” as they called it, he had the same reaction as just about everyone else there: He cracked up. “The early conversation,” he recalls, “was laughter.”

If Viagra was going to become anything but a punch line, Brinkley needed a launch team with the right mix of brash and style to handle it. And Pfizer had just the odd couple for the job: Rooney Nelson and Dr. Sal. “Have you ever seen that Arnold Schwarzenegger movie Twins?” Nelson says with a laugh. “We were Twins. He’s sort of a short, chubby, Italian, gregarious guy, and I’m this kind of tall, black, not-that-friendly guy that’s all about business.”

Nelson, an up-and-coming marketer at Pfizer, not only had the right edge to launch Viagra; he also had the perfect connections. He’d spent the past couple years working on Cardura, a treatment for the symptoms of enlarged prostates, and had cultivated relationships with urologists around the country, the exact group they needed to endorse and, ultimately, prescribe Viagra. It would be his job to convince them.

Dr. Sal was the ideal complement to Nelson. A wry middle-aged clinical pharmacist with five kids and two degrees from Columbia, he was Pfizer’s director of external relations, the medical expert responsible for managing the company’s image and reputation—two things that Viagra, more than any other drug he’d encountered in his eighteen years there, put at risk. “Pfizer then was still a very, very conservative company with very conservative roots,” he says, “and we were about to go off and sell a drug that was for sex.” With Dr. Sal’s medical expertise and Nelson’s marketing flair, it would be up to the two of them to sell the sex drug to the world.

What the hell is this? I don’t know what it’s doing to my brain.” The feedback from the men in the early Viagra focus groups went along these lines. “They were horrified,” as Nelson puts it. “The first reactions were ‘You’re kidding, right?’ You know: ‘Where’s the camera? I’m on Candid Camera.’”

The volunteers in the clinical trials were also skeptical. Nelson and Dr. Sal sat eagerly in a urologist’s office one day as ten patients anxiously filed in. But the goal wasn’t just to make money. There was something deeper that both of them recognized. Impotence was a real problem, one that, by being overlooked, was condemning generations, including the legions of baby boomers, to lives of frustration.

The men had volunteered to be part of one of Viagra’s early clinical trials, a first step toward bringing it to market. It was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial, which meant neither the physician nor the patient knew who’d be getting a placebo. After taking the drug, the patient received what was called “visual sexual stimulation.” The VSS of choice: Debbie Does Dallas. “I’d like you to watch it,” Nelson would tell the patient, “and I want to see if you get an erection or not. If you get an erection, there’s no cameras or anything, just so you know. If you have an erection, you know, feel free to masturbate. Here’s a vial. When you’re done, could you put the ejaculate, the semen, in that vial, close it up, and come back out?”

To determine what, if any, impact Viagra had on ejaculation, the team had to measure the amount and consistency of the semen. It was still so new that they had no idea what might happen. “You don’t know what this drug is doing,” Nelson says. What it was doing was something they’d never anticipated. Some patients reported that they were having blue-tinted vision, a condition known as cyanopsia. It turned out that one of the enzymes restricted by Viagra in order to create an erection caused sensitivity in some rod cells in the eye, causing some subjects to temporarily pick up more strands of blue light. A more lasting symptom presented in the volunteers who reported not just erections but four-hour ones—a temporary side effect that many patients didn’t mind. “Most people thought it was kind of cool,” Nelson says.

With the trials showing positive results, they had to find the right allies to get behind Viagra. In pharmaceutical marketing, just like in any other culture or industry, there are the whales, the big shots whose vote of confidence is essential to a new product’s success. The group consisted of the high-powered, high-priced medical practitioners: the heart surgeons, neurosurgeons, and the like. At this time, the 1990s, pharma companies had their own kind of legitimized payola—spending millions to wine and dine doctors into endorsing their meds.

To sell an erection drug, however, meant swaying the doctors who were way lower down the pecking order: the urologists. Compared with brain surgeons and cardiologists, urologists were the Dunder Mifflin of the pharma world: nerdy, unsexy, and unaccustomed to the warm fuzz of marketing crews. But that was about to change.

The mid-nineties were the heyday for pharmaceutical junkets, but Viagra marked the first time that unglamorous urologists were the ones being seduced. Pfizer would fly a dozen of them to an all-expenses-paid weekend at the Breakers in Palm Beach, Florida, and give them $2,500 each for their time. Pfizer could easily spend $200,000 per trip to entice them. “Urologists, they had never really been to places like that; they had never eaten like that; they had never drank like that,” Nelson says. “So you had a really primed group that was receptive to hearing your message.”

Over dirty martinis and lollipop lamb chops, Nelson would look out into the room and wonder how he was going to energize them. He pitched them on how he was going to make them as cool and desirable as open-heart surgeons. “This is an opportunity for you to be at the cutting edge of what could be the most revolutionary product in a long time in medicine,” he said. But there was one problem, they quickly told him: They never talked about sex with their patients. There was no reason to discuss impotence, because they had no remedy. “No physician asks about things that they can’t treat,” as Nelson puts it. “It was a wall of silence.”

The only way to succeed was to break the wall. He and the team developed what Dr. Sal called a series of “doorknob conversations,” named after that moment when men, often on the way out of the doctor’s office, would finally find the courage to ask about a cure for impotence. Their solution: Be straight with them. “Why don’t we just make this real simple and say, ‘If they think they have it, give them the medicine, tell them how to take it, set realistic expectations, and let them go for it,’ ” Dr. Sal says the conversation went. “And it’s either going to work or it’s not going to work.”

But while Dr. Sal and Nelson were making headway with urologists, they were encountering mounting skepticism within Pfizer. “Some medical groups felt that maybe we shouldn’t be marketing such trivial medicine,” Dr. Sal says. “But as the old joke goes, it’s only trivial if you don’t have the problem.”

Part of the issue, they realized, was semantics. No guy wanted to tell his doctor he was impotent. The word had too many negative overtones: weakness, helplessness, sterility. “In the early days,” says Brinkley, “just talking about impotence was taboo. You couldn’t even say the word penis.” They needed to come up with something better than impotence. Viagra’s medical team came back with just the fix: erectile dysfunction. It was perfect, they thought. “Impotence makes you feel like you did it to yourself,” as Nelson puts it. “Erectile dysfunction feels like it’s happening to you.”

This is blasphemy! This is immoral!”

Nelson and Dr. Sal listened patiently inside a conference room at the Helmsley hotel, overlooking Central Park, as another religious advocate told them what Pfizer could expect if Viagra ever got released. They’d assembled a roundtable of deacons, pastors, rabbis, and others to gauge their reactions to the boner pill. It was part of their due diligence for this uncharted territory, an important litmus test for what kind of resistance they’d meet by releasing the drug.

“There was concern that there might be religious objection,” says Brinkley, who’d had feelers out all the way up to the Vatican for a response. At this roundtable, it was already going south. “Why would you even do this?” one clergyman asked in dismay. “If that type of product ever comes on the market, I will organize protests against it.”

It seemed like a very real possibility that the launch could trigger a kind of “sex panic,” Brinkley says, from the moral majority. “They don’t want insurance or tax dollars paying for people’s boners.” It seemed they were also prepared to sensationalize Viagra, alleging that it would give men erections and also drive them to sex-crazed sprees that would spread AIDS. “As a gay man,” Brinkley says, “there was a fair amount of eye rolling that went on behind closed doors.”

They were also getting flak from inside. As word spread throughout Pfizer, Nelson and Dr. Sal began hearing more and more jokes and derisive comments from coworkers they passed in the halls. “We’re going to be a laughingstock,” one person would say. “Are we going to have Playboy Bunnies in the lobby?” joked another. Others were more pointed. “Are you guys crazy?” they’d ask. In Nelson’s estimation, the cards were stacking against them. “Fifty percent of the people within the company that knew what was going on thought it would never launch and never should launch,” he says.

Normally, when launching a new drug, a company would take pains to methodically introduce it to the world in advance, prepping the market, doing press, and so on. But Viagra was too volatile to leave vulnerable to these elements. So the team made a counterintuitive—if not seemingly harebrained—decision: They would launch completely in stealth, going public with it only twenty-four hours later if and when it was approved. “I had an epiphany, a eureka moment,” Nelson says. “The less we talk about this, even internally, the better we are.”

Discreetly, the team refined this strategy in thousands of focus groups. They narrowed it down to three possible ways—or “product profiles”—to present Viagra to the world. The first option was the most direct: It’s a drug that can cause erections and enable men who have lost their ability to have sex. The second was more scientific: Viagra can treat a disease called erectile dysfunction and allow men to return to normal physiological capacity. The third took a different approach completely, skirting the details of the drug and focusing instead on its delivery system: For the first time, there’s a pill that can be used to treat a condition that has always been treated by invasive surgeries.

After thousands of focus groups, they arrived at the answer: option number three. Viagra is a pill—safe, cheap, and easy. A guy would merely get a sample, pop it into his mouth, and see how it worked. This was the perfect way to get men to look at the drug. As Nelson puts it, “I’ll try it! And if it doesn’t work, who gives a fuck?”

The strategy succeeded. In the later focus groups, the pill hit big. By February 1998, Pfizer was ready to launch the drug. But there was one important hurdle remaining: approval by the Food and Drug Administration. Pfizer had spent nearly $100 million on Viagra up to that point, and there was no guarantee that the world’s first erection pill wouldn’t go limp.

On March 27, 1998, Nelson, Dr. Sal, Brinkley, and the dozen others on Viagra’s core team gathered around a fax machine in a conference room in Pfizer’s New York headquarters. They were awaiting a message from the FDA regarding whether their eighteen months of efforts had finally paid off. Shortly before noon, the answer spooled out. A lawyer ran her eyes over the page and read it aloud: “The FDA has approved sildenafil citrate for the use of erectile dysfunction in men.”

Nelson shouted, “Oh my God! Fuck me! Yeah!” He fell on the floor in relief, joined by the others. But they couldn’t celebrate for long. The FDA approval meant it was time to launch a drug that still had yet to be announced to the world.

Right on the heels of the approval, there was a more pressing matter: the side effects required to be listed on the label. The regulatory board had hit them with a black-box warning about taking Viagra with nitrates—a combination that could result in a heart attack. Most companies would try to bury the black box as much as possible. But Brinkley surprised his team. He told the group to lead with it. “We’re going to encourage people that if you’re on a nitrate, do not take Viagra,” he said. “That’s going to be the first thing we’re going to say.”

Nelson thought Brinkley was “batshit crazy.” There was no precedent for such a maneuver. But Brinkley, Nelson recalls, held firm. “Rooney,” he said, “you have to trust me on this.” His reasoning was that Viagra was going to be such a hit that they didn’t need to risk hiding anything about it, even if it meant equating sex with death.

With everything ready to go, the team booked a massive launch meeting at the World Center Marriott in Orlando, Florida, to introduce Viagra to Pfizer’s three thousand sales representatives. The average sales rep was a good-looking twenty-five-year-old—“The guy looked like a quarterback, and the girl looked like freaking Candy the cheerleader,” Nelson says—but that didn’t make the challenge any easier. “We needed to make them comfortable with talking about sex,” he says. They did this by getting everyone used to saying all the right words. They went around the room and had everybody say erection five times. “Erection! Erection! Erection! Erection! Erection!”

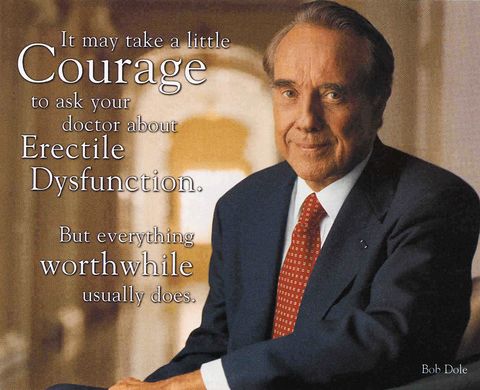

They had to get the general public talking, too. They needed someone who could deliver the message soberly and credibly. During the clinical trials, they learned from a urologist at Walter Reed that former senator and presidential candidate Bob Dole was interested in participating. Dole had been partially paralyzed during World War II and was himself suffering from erectile dysfunction. After trying Viagra successfully, he was more than ready to speak out on behalf of the drug to help others. It was just what the team needed. “The important thing was to normalize the medical condition,” Brinkley says, and Dole proved to be the ideal messenger.

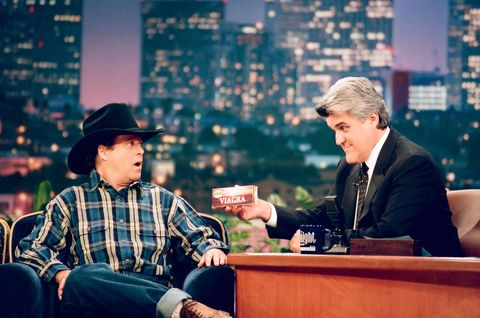

When Viagra finally hit the market, for eight to twelve dollars a pill, it was an instant phenomenon. As expected, it also became the butt of late-night-talk-show jokes and provoked the ire of the moral majority. But it sold wildly. Pharmacists reported filling ten thousand prescriptions a day, which easily outpaced scripts for the launches of top drugs such as Prozac and Rogaine. Viagra sales would reach $1 billion in its first year. “It’s the fastest takeoff of a new drug that I’ve ever seen,” Michael Podgurski, then the director of pharmacy for Rite-Aid, gushed to Time. Newsweek called it “the hottest new drug in history.”

For the team behind the scenes who launched Viagra, the success gave them a deeper satisfaction, too. Dr. Sal was eating at a steakhouse in Monroe, Louisiana, with his wife when he overheard some men at a nearby table talking about erectile dysfunction. It filled him with pride. “My God,” he said. “We’ve accomplished one of our goals, which is to talk about this as a real medical problem, not as a sexually dirty kind of thing, and take away some of the stigma associated with older persons having intimacy.”

Nelson learned four rules for launching something that’s never been done before. “Number one, expect to be laughed at if you’re doing something that’s going to be a breakthrough,” he says. “Number two, be real wary of experts; they’re going to tell you all the reasons why that thing’s not going to work. The third thing: Have people on the team who really understand the business you’re in.” And, finally, he says, be prepared to be hated. “If you expect to change the world, you’re going to get a lot of love, but you’re going to get a lot of hate. You got to run the math. The hate’s probably going to be a fraction of the love.”

And as Dr. Sal learned, there was plenty of love to go around. Not long after Viagra came out, his father asked him if he could hook him up. “Hey, can you get me some samples?” his dad asked.

“Absolutely not!” his mother replied sardonically. “Don’t even think about it, Sal.”

Today, twenty years after Viagra’s launch, it’s never been easier to get the little blue pill. Pfizer just released its nonprescription version, dubbed Viagra Connect, in Britain, the first country to approve over-the-counter sales of Viagra.

Though the patent on Viagra doesn’t expire until 2020, Pfizer negotiated a deal that allowed Teva Pharmaceuticals to begin selling a generic version last December. Not only is the pill considerably less expensive; it’s now all the more accessible. Roman, a new start-up, is an app that screens men for erectile dysfunction and gets a prescription delivered right to their door.

While Viagra is going mainstream like never before, there’s more opportunity on the horizon for treating other such maladies. “There are still a lot of sexual dysfunctions where we don’t have treatment,” Osterloh says, “such as lack of sexual desire in men and women.” An estimated twelve million women suffer from sexual desire disorder. The leading contender for treatment is bremelanotide, which is being developed by AMAG Pharmaceuticals and Palatin Technologies. They have completed successful trials and hope to have it available by 2019.

When asked what’s coming next for men, Nelson, who has since left Pfizer to run his own marketing firm, cracks a devilish grin. “You really want the dark-web version of this?” he asks. The future, he goes on, will feature artificially intelligent sexbots and drugs that will enhance the experience further. “There’s going to be a pill that increases not only erections but pleasure,” Nelson says. “That’s going to be the cocaine of sex. It’s the ultimate pill.”