A few months after the World Trade Center attacks, a strange message appeared on a U.S. Army computer: “Your security system is crap,” it read. “I am Solo. I will continue to disrupt at the highest levels.”

Solo scanned thousands of U.S. government machines and discovered glaring security flaws in many of them. Between February 2001 and March 2002, Solo broke into almost a hundred PCs within the Army, Navy, Air Force, NASA, and the Department of Defense. He surfed around for months, copying files and passwords. At one point he brought down the U.S. Army’s entire Washington, D.C., network, taking about 2000 computers out of service for three days. U.S. attorney Paul McNulty called his campaign “the biggest military computer hack of all time.”

But despite his expertise, Solo didn’t cover his tracks. He was soon traced to a small apartment in London. In March 2002, the United Kingdom’s National Hi-Tech Crime Unit arrested Gary McKinnon, a quiet 36-year-old Scot with elfin features and Spock-like upswept eyebrows. He’d been a systems administrator, but he didn’t have a job at the time of his arrest; he spent his days indulging his obsession with UFOs.

In fact, McKinnon claimed that UFOs were the reason for his hack. Convinced that the government was hiding alien antigravity devices and advanced energy technologies, he planned to find and release the information for the benefit of humanity. He said his intrusion was detected just as he was downloading a photo from NASA’s Johnson Space Center of what he believed to be a UFO.

Despite the outlandishness of his claims, McKinnon now faces extradition to the United States under a controversial treaty that could land him in prison for years—and possibly for the rest of his life. The case has transformed McKinnon into a cause célèbre. Supporters have rallied outside Parliament with picket signs. There are “Free Gary” websites, T-shirts, posters. Rock star David Gilmour, the former guitarist for Pink Floyd, even recorded a benefit song in his honor.

Why the spectacle? McKinnon has been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism. The range of conditions known as autism spectrum disorders currently affects 1 out of 110 American children, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Researchers say that diagnoses of these problems are increasing faster than those of any other developmental disorder. Medical researchers still don’t understand the cause and are nowhere near a cure.

People with Asperger’s are often highly intelligent, and many have an accomplished understanding of complex systems, causing researchers to study a possible link between autism and engineering. But Asperger’s sufferers have severe difficulty reading social cues and grasping the impact of their often-obsessive behavior. “There have been an inordinate number of young men with Asperger’s who have gotten in trouble with the law,” says autism expert Rhea Paul of the Yale School of Medicine Child Study Center. “It’s difficult for them to intuit moral decisions that may come more easily to others,” she says. McKinnon’s lawyers argue that his criminal behavior was a result of his disorder, and they have asked courts to judge him with leniency as a result.

Meanwhile, a debate is raging over the role of Asperger’s in his crime. Former UK prime minister Gordon Brown is among those who have said that McKinnon deserves sympathy. Others believe the disorder does not merit a lesser sentence. “There is a need for stronger penalties for hackers,” says Amit Yoran, former National Cyber Security Division director within the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. “Without consequences for people’s actions, an entire underpinning of modern society is at risk.”

McKinnon’s case raises a new and provocative question: Could Asperger’s become the insanity defense for the hackers of the digital age?

McKinnon had always been fascinated by outer space. A puckish, bright boy from Glasgow, he would ask his parents technical questions about the distance between planets and the scientific names of stars. “It was the kind of stuff a toddler didn’t usually talk about,” McKinnon’s mother, Janis Sharp, tells IEEE Spectrum. “It was very unusual.”

But McKinnon’s differences went far beyond his obsession with astronomy. Whenever Sharp took him on a bus, the boy would shout uncontrollably. By the age of 10, he had grown fearful of the outdoors and spent hours in his room devouring books on space or listening to music. When Sharp, a musician recently divorced and living with Gary in London, begged him to join the neighborhood kids outside, McKinnon would plead, “Please don’t make me go out to play.” The boy was troubled, but his obsessions seemed to give him a sense of control and peace. Though not a naturally gifted musician, he spent hours at the piano teaching himself to play Beethoven’sMoonlight Sonata and complicated Beatles songs. Sharp couldn’t believe her ears. “We were knocked out,” she says.

At age 14, he taught himself to code video games—set in outer space, of course—on his Atari computer. McKinnon joined the British UFO Research Association and found a community of like-minded space buffs. When he learned that his stepfather had grown up in Bonnybridge, an English town famous for UFO sightings, he grilled him for information, his mother recalls.

But while McKinnon dreamed of flying saucers, he struggled with everyday life on Earth. After dropping out of secondary school, he floated between jobs in computer technical support. The childhood fear of public transportation had grown even worse, and McKinnon suffered fainting spells when he had to ride the London Underground. Although he lived with his childhood sweetheart, a bright and amiable girl, he couldn’t bear the thought of starting a family.

“How can I be responsible for a baby?” he aked his mother. As his relationship with his girlfriend waned, McKinnon grew increasingly despondent, losing his job and refusing help. His mother feared that his depression could lead to suicide. But McKinnon made a key discovery: the new world being created on the nascent Internet of the mid-1990s. “That’s when he started looking online for information on aliens,” Sharp recalls. “It was his escape.”

After reading The Hacker’s Handbook, the classic 1980s how-to book for computer hackers, McKinnon decided to do a bit of sleuthing himself. Late at night in his darkened bedroom he began trying out the book’s suggested techniques, and in 2000 he decided to look for UFO evidence on the U.S. government’s computer systems.

McKinnon put his powers of concentration to use, obsessively researching ways to break into the machines. Using the Perl programming language, he wrote a small script that he says allowed him to scan up to 65 000 machines for passwords in under 8 minutes. After dialing up the government systems, he ran the code and made an astonishing discovery: Many federal workers failed to change the default passwords on their computers. “I was amazed at the lack of security,” he later told the Daily Mail.

On these unsecure machines, McKinnon installed a software program calledRemotelyAnywhere, which allows remote access and control of computers over the Internet. McKinnon could then browse through the machines at his leisure and transfer or delete files. Because he was able to monitor all activity on the computers, he could log off the moment he saw anyone else logging on.

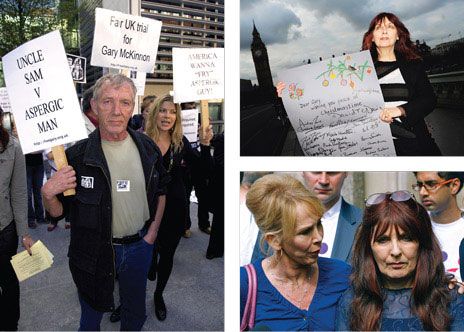

Photos: Clockwise from left: Press Association/AP Photo (2); Oli Scarff/Getty Images

STAUNCH SUPPORTERS: McKinnon’s father [left] participates in a rally; his mother [top right] holds a card signed by well-wishers; actress Trudie Styler stands by McKinnon’s mother [bottom right].

With his fixation overpowering him, McKinnon surfed through government computers from Fort Meade to NASA’s Johnson Space Center in his quest for E.T. He claimed he had found a list of the U.S. Navy’s “nonterrestrial officers,” as well as a photo of a cigar-shaped UFO studded with geodesic domes (a photo he couldn’t save, he said, because it was in Java script). After a lifetime of obsessing about UFOs, he was now feeding his habit as never before. He was also savoring the thrill of the hack. “You end up lusting after more and more complex security measures,” he told The Guardian in 2005. “It was like a game. I loved computer games. I still do. It was like a real game. It was addictive. Hugely addictive.”

But the game finally ended. The U.S. Department of Justice hasn’t publicly discussed how it became aware of McKinnon, but he believes his intrusion was detected when he logged onto a computer at the Johnson Space Center at the wrong time. He has said that his access to that computer was immediately cut off; he believes the government then discovered the RemotelyAnywhere software on the machine and traced its purchase to his e-mail address.

In March 2002, his mother’s phone rang. “I’ve been arrested,” McKinnon said. Sharp’s throat constricted—what had her son gotten himself into? But McKinnon told her not to worry. The UK National Hi-Tech Crime Unit had arrested him under the Computer Misuse Act, McKinnon said, which carried a relatively benign sentence of six months’ community service. “I don’t need to get a lawyer,” McKinnon assured his mother. But that statement would prove incredibly naive.

In 2005 the United States moved to extradite McKinnon under an extradition treaty created after the attacks of September 11 to aid in the prosecution of suspected terrorists. The U.S. Department of Justice doesn’t care about his bizarre motivations for the hack, and it claims that the damage he caused was severe. He is charged with causing over US $700 000 in damages ($5000 per machine) and deleting at least 1300 user accounts and operating systems files. It was his deletion of critical files that reportedly crashed the U.S. Army’s network in Washington, D.C., for three days (McKinnon has claimed he did this by accident). The Department of Justice has argued that McKinnon’s conduct significantly disrupted government functions and put national defense and security at risk.

McKinnon faces a potential sentence of up to 70 years behind bars in a U.S. prison. When his family heard the news, they were “stunned and frightened,” Sharp recalls. As word spread online and in the UK media, people began to protest that the punishment was excessive. Sharp organized a campaign pleading for help for her son and got it in a most surprising way. A woman who had seen McKinnon on TV thought he exhibited signs of Asperger’s syndrome and suggested that he get a psychiatric examination.

Like many people, Sharp was unfamiliar with the condition. “I thought it had something to do with being retarded,” she says. But when she thought about her son’s unusual behavior over the years—his fear of traveling, his obsessive behavior, his lack of social skills—it started to add up. McKinnon agreed to be evaluated by one of the world’s foremost experts, Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge.

Over the course of his research on autism, Baron-Cohen has become an authority on the emerging connection between Asperger’s and engineering. “It makes sense that someone with Asperger’s might be quite skilled at hacking,” he tells Spectrum, “simply because one of the things they share is an understanding of systems, including computer systems.” Baron-Cohen has found that more than 50 percent of people with Asperger’s have an obsessive interest in technology, physics, and space. He has also discovered that autistic children are more likely to have engineer fathers and grandfathers than are normal children. He has even speculated that the rising incidence of autistic spectrum disorders may stem from a modern tendency for engineers to marry either other engineers or people who think like them.

After a 3-hour examination, Baron-Cohen found that McKinnon fit the profile. “He has got the classic patterns of Asperger’s,” he says. “[McKinnon has] a very narrow attention span and got totally obsessed searching for information about UFOs….The other feature that was pretty classic was this social naïveté, not thinking about how he might be perceived by others.” Sharp says her shock at the news quickly faded to a sense of relief, as the diagnosis gave reason for behavior that had seemed so unreasonable for so long. “It began to make sense: how Gary was, how he can live in a dream world, how obsessed he was with what he did,” she says.

Word spread of McKinnon’s diagnosis, and he became an icon of Asperger’s. In March 2009,Sting told the Daily Mail that it was “a travesty of human rights that Gary McKinnon finds himself in this dreadful situation. The British government is prepared to hand over this vulnerable man without reviewing the evidence.” Members of Parliament lobbied on his behalf, including Andrew MacKinlay,who would later resign in protest after McKinnon lost appeal after appeal in the British courts. MacKinlay didn’t think his fellow MPs were doing enough to protect McKinnon from being extradited when he was far from a terrorist.

McKinnon’s diagnosis has not deterred the U.S. government from pursuing extradition. A spokesperson for the Department of Justice Criminal Division says the department can’t comment on the unfolding case but stands by the indictment [PDF].

McKinnon wants to be tried for his crimes in a British court and has repeatedly asked the UK government to halt the extradition. In 2010 the UK home secretary finally agreed to review the case; she is also arranging for an independent medical expert to evaluate McKinnon. Baron-Cohen says the government may be making a life-or-death decision. After extensively interviewing McKinnon, he found him to be prone to depression and suicide. “If Gary McKinnon is sent to the U.S.,” he said, “I fear he will kill himself.”

Karen Todner, McKinnon’s attorney, says the home secretary should carefully consider McKinnon’s mental faculties in making the decision. “Asperger’s is not an excuse,” Todner says, “but it certainly puts his actions in more of a clear light.” As he awaits his legal fate, McKinnon remains under psychiatric care. He is barred from using his computer, and he refuses to speak with friends, family, or the press.

Some question the role of the syndrome in the crime. A blogger on AspieWeb, an online hub for people with Asperger’s, challenges McKinnon for using the syndrome as “a scapegoat for your actions that are very illegal in order to get away with what you did. As someone who has Asperger’s your actions are very offensive.”

Courts are beginning to grapple with the Asperger’s defense. In August 2009, Viacheslav Berkovich, a 34-year-old Russian immigrant in the United States diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome, received a reduced sentence after being convicted of hacking into a trucking company’s computers in California. In 2008, a defense witness for Hans Reiser, a computer programmer convicted of brutally murdering his wife, testified that Reiser might have Asperger’s. Defense attorneys also used the Asperger’s defense for Lisa Brown, a 22-year-old convicted of murdering her mother. “Someone with Asperger’s syndrome could still plan an act but, because of deficiencies in their social imagination, might be unable to see what the consequences of those actions might be,” a psychiatrist said of Brown, who received a life sentence regardless.

Will Asperger’s become a new kind of insanity defense? “The judicial system has not yet come to terms with Asperger’s syndrome,” says Brenda Myles Smith of the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders. “We need to ensure that [the courts are] educated about this.”

Part of the problem is that Asperger’s is still relatively new to professionals and educators; it was added to the World Health Organization’s diagnostic manual only in 1992. “The majority of people with Asperger’s go undiagnosed,” says Pat Schissel, president of the Asperger Syndrome and High Functioning Autism Association. “We need greater awareness of this in medical schools and the education system.”

Maybe, just maybe, raising awareness of Asperger’s could even curb more cybercrimes in the future. “It’s an issue we should get on the table and start to address,” says Jeff Sell, the Autism Society‘s general counsel and vice president of public policy. “These folks are very gifted when it comes to technology, and the potential is there for some type of concern.”